Finally I am done with the first volume of The Man Without Qualities. It is obviously an extraordinary book. When I picked it up, I hadn't thought that I would read it this far and now after reading more than 700 pages I am ready to plunge into the next volume too and to read through the unfinished drafts and manuscripts and alternate endings (another thousand pages).

Anyway, I will try to write a summary of the first volume with my own personal impressions sometime later. For now here is a (loooong) extract from towards the end of the book. I am going to return the book back to the library so I thought I should copy something here. It can be read without much context too. Basically Ulrich is the main character in the novel, the titular man without qualities. He is very sharp and has an ironic and detached attitude to everything around him. He is also irresistibly attractive to women! Gerda on the other hand is a minor character, a girl in her early twenties and sexually immature. It is basically an analysis of PCGA (Pre-Coital Guilt Attack). Okay, I made that up. But I bet there is some term like that in pyschiatry. Also a good illustration for the mind-body problem.

Here it is:

******

[But]Ulrich had put his arm around her again because, knowing that he had something important to do since hearing the news about

Arnheim, he first had to finish this episode with Gerda. He was not at all reconciled to having to go through everything the situation called for, but he immediately put the rejected arm around her again, this time in the wordless language which, without force, states more firmly than words can do that any further resistance is useless. Gerda felt the virility of that arm all the way down her spine. She had lowered her head, with her eyes fixed on her lap as though it held, gathered as in an apron, all the thoughts that would help her to reach that "human understanding" with Ulrich before anything could be allowed to happen as a crowning act. But she felt her face looking duller and more vacuous by the moment until, like an empty husk, it finally floated upward, with her eyes directly below the eyes of the seducer.

He bent down and covered this face with ruthless kisses that stir the flesh. Gerda straightened up as if she had no will of her own and let herself be led the ten steps or so to Ulrich's bedroom, leaning heavily on his as though she were wounded or sick. Her feet moved, one ahead of the other, as if she had nothing to do with it, even though she did not let herself be dragged along but went of her own accord. Such an inner void despite all that excitement was something Gerda had never known before; it was as if all the blood had been drained from her; she was freezing, yet in passing a mirror that seemed to reflect her image from a great distance she could see that her face was a coppery red, with flecks of white. Suddenly, as in a street accident when the eye is hypersensitive to the whole scene, she took in the man's bedroom with all its details. It came to her that, had she been wiser and more calculating, she might have moved in as Ulrich's wife. It would have made her very happy, but she was groping for words to say that she was not out for any advantage and had come only to give herself to him; yet the words did not come, and she told herself that this had to happen, and opened the collar of her dress.

Ulrich had released her. He could not bring himself to help undress her like a fond lover and stood apart, flinging off his own clothes. Gerda saw the man's tall, straight body, powerfully poised between violence and beauty. Panic-stricken, she noticed that her own body, still standing there in her underthings, was covered with

gooseflesh. Again she groped for words that might help her, that might her less of a miserable figure where she stood. She longed to say something that would turn Ulrich into her lover in a way she vaguely imagined as dissolving in infinite sweetness, something one could achieve without having to do what she was about to do, something as blissful as it was indefinable. For an instant she saw herself standing with him in a field of candles growing out of the earth, row upon row to infinity, like so many pansies, all bursting into flame at her feet on signal. But as she could not utter a single word of all this, she went on feeling painfully unattractive and miserable, her arms trembling, unable to finish undressing; she had to clamp her bloodless lips together to keep them from twitching weirdly without a sound.

At this point Ulrich, who saw her agony and realized that the whole struggle up to now might come to nothing, went over to her and slipped off her shoulder straps. Gerda slip into bed like boy. For an instant Ulrich saw a naked adolescent in motion; it affected him no more, sexually, that the sudden blinking of a fish. He guessed that Gerda had made up her mind to get it over with because it was too late to get out of it, and he had never yet perceived as clearly as in the instant he followed her into bed how much the passionate intrusion into another body is a sequel to child's liking for secret and forbidden hiding places. His hands encountered the girl's skin, still bristling with fear, and he felt frightened too, instead of attracted. This body, already flabby while still unripe, repelled him; it made no sense to do what he was doing, and he would have liked nothing better than to escape from this bed, so that he had to call to mind everything he could think of that would help him to see it through. In frantic haste he summoned up all the usual reasons people find nowadays to justify their acting without sincerity, or faith, or scruple, or satisfaction; and in abandoning himself to this effort he found, not, of course, any feeling of love, but a half-crazy anticipation of something like a massacre, a sex-murder or, if there is such a thing, a lustful suicide, inspired by the demons of the void who lurk behind all of life's images. This reminded him of his brawl with the hoodlums that night he met

Bonadea, and he decided to be quicker this time. But now something awful happened. Gerda had been gathering up all her inner resources to

alchemize them into willpower with which to resist the shameful terror she was suffering, as though she were facing her execution; but the instant she felt Ulrich beside her, so strangely naked, his hands on her bare skin, her body flung off all her will. Even while somewhere deep inside she still felt a friendship beyond words for him, a trembling, tender longing to put her arms around him, kiss his hair, follow his voice to its source with her lips; and imagined that to touch his real self would make her melt like a fragment of snow on warm hand--but it would have to be Ulrich she knew, dressed as usual, as appeared in the familiar setting of her parental home, not this naked stranger whose hostility she sensed and who did not take her sacrifice seriously even as he gave her no time to think what she was doing--Gerda suddenly heard herself screaming. Like a little cloud, a soap bubble, a scream hung in the air, and others followed, little screams expelled from her chest as though she were wrestling with something, a whimpering from which cries of

ee-ee bubbled and floated off, from lips that grimaced and twisted and were wet as if with deadly lust. She wanted to jump up, but she couldn't move. Her eyes would not would not obey her and kept sending out signals without permission. Gerda was pleading to be let off, like a child facing some punishment or being taken to the doctor, who cannot go one step farther because it is being torn and convulsed by its own shrieks of terror. Her hands were up over her breasts, and she was menacing Ulrich with her nails while frantically pressing her long thighs together. This revolt of her body against herself was frightful. She perceived it with utmost clarity as a kind of theatre, but she was also the audience sitting alone and desolate in the dark auditorium and could do nothing to prepare her fate from being acted out before her, in a screaming frenzy; nothing to keep herself from taking the lead in the performance.

Ulrich stared in horror into the tiny pupils of her veiled eyes, with their strangely unbending gaze, and watched, aghast, those weird motions, in which desire and taboo, the soul and the soulless, were indescribably intertwined. His eye caught a fleeting glimpse of her pale fair skin and the short black hairs that shaded into red where they grew more densely. It occurred to him that he was facing a fit of hysteria, and he had no idea how to handle it. He was afraid that these horribly distressing screams might get even louder, and remembered that such a fit might be stopped by an angry shout or even by a sudden, vicious slap. Then he thought that this horror might have been avoided somehow led him to think that a younger man might persist in going further with Gerda even in these circumstances. "That might be a way of getting her over it," he thought, "perhaps it's a mistake to give in to her, now that the silly goose has let herself in too deep." He did nothing of the sort; it was only that such irritable thoughts kept zigzagging through his mind while he was instinctively whispering an uninterrupted stream of comforting words, promising not to do anything to her, assuring her that nothing had really happened, asking her to forgive him, at the same time that all his words, swept up like chaff in his loathing of the scene she was making, seemed to him so absurd and undignified that he had to fight off a temptation to grab an armful of pillows to press on her mouth and choke off these shrieks that wouldn't stop.

At long last her fit began to wear off and her body quieted down. Her eyes brimming with tears, she sat up in her bed, her little breasts drooping slackly from a body not yet under mind's full control. Ulrich took a deep breath, again overcome with repugnance at the inhuman, merely physical aspects of the experience. Gerda was regaining normal consciousness; something bloomed in her eyes, like her eyes, like the first actual awakening after the eyes have been open for some time, and she stared blankly ahead for a second, then noticed that she was sitting up stark naked and glanced at Ulrich; the blood came back in great waves back to her face. Ulrich couldn't think of anything better to do than whisper the same reassurances to her again; he put his arm around her shoulder, drew her to his chest, and told her to think nothing of it. Gerda found herself back in the situation that had driven her to hysteria, but now everything looked strangely pale and forlorn: the tumbled bed, her nude bed in the arms of a man intently whispering to her, the feelings that had brought her to this. She was fully aware of what it all meant, but she also knew that something horrible had happened, something she would rather not focus on, and while she could tell that Ulrich's voice sounded more tender all it meant was that he regarded her as a sick person, but it was he who had made her sick! Still, it no longer mattered; all she wanted was to be gone from this place, to get away without having to say a word.

Touching the Void: Touching the void tells the real life story of Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, two Brits in their early twenties, who go on a mountaineering expedition in the Peruvian Andes. The 6344 metres high Siula Grande mountain has never been climbed before and the two men want to make a name for themselves. After three and half days of continuous climbing they both make it up to the summit but on the way down Joe meets with an accident and fractures his leg. Simon tries to bring his friend down with him initially but after some further mishaps has to take the painful decision of cutting the rope and making his way back down alone. The real story starts from here about how Joe survives against all odds even after having "touched the void", i.e came face-to-face with death. It could easily have become one of those cheesy stories about how inspiration and the will to succeed against all odds leads to success etc but it does not mainly because it is so awesomely shot. The story is narrated entirely through the voices of the (real) Joe and Simpson and their third partner who was in-charge of the base camp. The rest of the film is a dramatic reconstruction of the actual events. And what a reconstruction it is! If you have seen films like Cliffhanger or Vertical Limit and think you have seen enough, wait till you see this one. Also the struggle and ordeal that Simon goes through, virtually crawling his way back to the base of the mountain, it makes one think afresh as to where does this will t0 survive come from? What is this elemental force that keeps him going against such insurmountable odds? Did he have something special psychologically? Must have been. That's why not all of us become mountaineers. Some reviews of the film here.

Touching the Void: Touching the void tells the real life story of Joe Simpson and Simon Yates, two Brits in their early twenties, who go on a mountaineering expedition in the Peruvian Andes. The 6344 metres high Siula Grande mountain has never been climbed before and the two men want to make a name for themselves. After three and half days of continuous climbing they both make it up to the summit but on the way down Joe meets with an accident and fractures his leg. Simon tries to bring his friend down with him initially but after some further mishaps has to take the painful decision of cutting the rope and making his way back down alone. The real story starts from here about how Joe survives against all odds even after having "touched the void", i.e came face-to-face with death. It could easily have become one of those cheesy stories about how inspiration and the will to succeed against all odds leads to success etc but it does not mainly because it is so awesomely shot. The story is narrated entirely through the voices of the (real) Joe and Simpson and their third partner who was in-charge of the base camp. The rest of the film is a dramatic reconstruction of the actual events. And what a reconstruction it is! If you have seen films like Cliffhanger or Vertical Limit and think you have seen enough, wait till you see this one. Also the struggle and ordeal that Simon goes through, virtually crawling his way back to the base of the mountain, it makes one think afresh as to where does this will t0 survive come from? What is this elemental force that keeps him going against such insurmountable odds? Did he have something special psychologically? Must have been. That's why not all of us become mountaineers. Some reviews of the film here. One Day in September: The Munich Olympics terrorist attack was in news last year because of the controversy surrounding the Steven Spielberg film Munich. Spielberg's film also had a brilliant reconstruction of what happened in Munich but the rest of the film was very naive, simplistic and cliched. This documentary is not really a reconstruction but is made entirely of actually footages from the tragic event. Michael Douglas in his sonorous voice provides the sparse commentary but rest of the time it is the events which speak for themselves directly. There is also a remarkable interview with one of the survivors of the Black September terrorist group responsible for the attacks. He performs the usual role of providing the other side of the story. There are also interviews of the German officials in charge of the negotiation and the rescue operation. Overall the Germans come out very bad in the end for the ineptness they showed. It is shocking to see how ridiculously ill prepared they were. There is also an interview with the wife of one of the murdered member of the Israeli team. It is all fused together so brilliantly that it is difficult to take your eyes off screen for even a second. It is relentless and horrifying and suspenseful, even though one already knows how the whole thing will end in advance. Like Touching the Void, this film was also directed by Kevin McDonald, who obviously looks like a very important filmmaking talent on the strength of just these two films. It also won the Oscar for the best documentary film in 2000. The Wikipedia page of the film here.

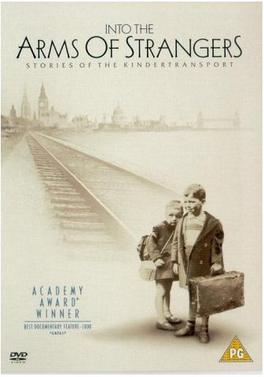

One Day in September: The Munich Olympics terrorist attack was in news last year because of the controversy surrounding the Steven Spielberg film Munich. Spielberg's film also had a brilliant reconstruction of what happened in Munich but the rest of the film was very naive, simplistic and cliched. This documentary is not really a reconstruction but is made entirely of actually footages from the tragic event. Michael Douglas in his sonorous voice provides the sparse commentary but rest of the time it is the events which speak for themselves directly. There is also a remarkable interview with one of the survivors of the Black September terrorist group responsible for the attacks. He performs the usual role of providing the other side of the story. There are also interviews of the German officials in charge of the negotiation and the rescue operation. Overall the Germans come out very bad in the end for the ineptness they showed. It is shocking to see how ridiculously ill prepared they were. There is also an interview with the wife of one of the murdered member of the Israeli team. It is all fused together so brilliantly that it is difficult to take your eyes off screen for even a second. It is relentless and horrifying and suspenseful, even though one already knows how the whole thing will end in advance. Like Touching the Void, this film was also directed by Kevin McDonald, who obviously looks like a very important filmmaking talent on the strength of just these two films. It also won the Oscar for the best documentary film in 2000. The Wikipedia page of the film here. Into the Arms of Stranger: On the eve of the second world war a remarkable rescue operation called Kindertransport saved the lives of over ten thousand Jewish children by taking them away from their homes in Central Europe and Germany to England, where they lived in foster homes and orphanages. A major part of the documentary is about the men and women, now in their sixties and seventies, telling their experiences of leaving home at such an age and landing up in an alien country. Judi Dench provides the necessary narration with her usual crispness. It is remarkable, the clarity and enthusiasm with which all of them tell their painful stories. A few of them were even reunited with their parents after the war but most of them were not so lucky. They knew the terrible truth about what had happened to their parents soon after the war ended. It is also tragic to think how many more lives could have saved. Only children were allowed because the British government thought that they wouldn't be of considerable burden to the national economy! And even then they had to go through lots of bureaucratic hassles. A similar proposal to bring children to US was quashed by the senate because they felt that the children belonged to their parents and they couldn't allow children to come on their own. It won the Oscar for the Best Documentary film too. This is the wikipedia page.

Into the Arms of Stranger: On the eve of the second world war a remarkable rescue operation called Kindertransport saved the lives of over ten thousand Jewish children by taking them away from their homes in Central Europe and Germany to England, where they lived in foster homes and orphanages. A major part of the documentary is about the men and women, now in their sixties and seventies, telling their experiences of leaving home at such an age and landing up in an alien country. Judi Dench provides the necessary narration with her usual crispness. It is remarkable, the clarity and enthusiasm with which all of them tell their painful stories. A few of them were even reunited with their parents after the war but most of them were not so lucky. They knew the terrible truth about what had happened to their parents soon after the war ended. It is also tragic to think how many more lives could have saved. Only children were allowed because the British government thought that they wouldn't be of considerable burden to the national economy! And even then they had to go through lots of bureaucratic hassles. A similar proposal to bring children to US was quashed by the senate because they felt that the children belonged to their parents and they couldn't allow children to come on their own. It won the Oscar for the Best Documentary film too. This is the wikipedia page.