In which I try to explain why I like Antonioni in pseudo-intellectual terms

My fanboyish ejaculations on Antonioni's films a couple of posts earlier drew startled responses from a couple of friends (Bhaya and Anurag, this is for you!). They felt that it deviated from the norms of pseudo-intellectual pretentions that this blog generally displays. And after all, being a pseudo-intellectual, how can you just "like" something without giving a proper theoretical justification or dropping a few names, preferably from the western tradition? Also, my saying that I like depressed and beautiful women was found to be shockingly childish. So this post is an exercise in damage control, an attempt to restore the reputation of being a pseudo-intellectual. In what follows I explain why I like Antonioni (specially those three films, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse) in a very pseudo-intellectualish way of course:

My fanboyish ejaculations on Antonioni's films a couple of posts earlier drew startled responses from a couple of friends (Bhaya and Anurag, this is for you!). They felt that it deviated from the norms of pseudo-intellectual pretentions that this blog generally displays. And after all, being a pseudo-intellectual, how can you just "like" something without giving a proper theoretical justification or dropping a few names, preferably from the western tradition? Also, my saying that I like depressed and beautiful women was found to be shockingly childish. So this post is an exercise in damage control, an attempt to restore the reputation of being a pseudo-intellectual. In what follows I explain why I like Antonioni (specially those three films, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse) in a very pseudo-intellectualish way of course:

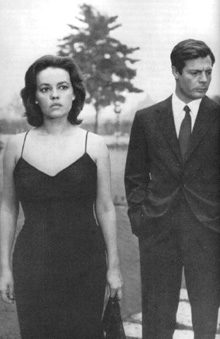

First, depressed beautiful women. Let me put it this way. I love the portrayal of a profound sexual melancholy in Antonioni's films, in his female characters specially. Sexual melancholy, as in, when you are feeling completely isolated, disconnected and alienated from your surroundings and yet deeply long for a serious erotic union with the Other. Or, in less pretentious terms, you are feeling sad, alone and horny all at the same time. Antonioni connects sexual desire with a general anxiety and uncertainty that the characters feel about everything and which gradually eats away at their souls. No wonder that Monica Vitti after being depressed in all these three films finally reaches mental asylum in Red Desert, which is a continuation of the trilogy.

Second, getting away from the classical concerns of character or narrative. Antonioni took narrative cinema away from straight storytelling, towards a realm where he could explore ideas in a more direct manner.  People looking for narrative closure and clean-cut explanations for character behavior will be disappointed with his films. What is important there, is the "mood", which Antonioni creates and sustains by employing very stylish camera work and scene compositions. And through this he explores the ideas in a purely visual manner. But what exactly are those ideas? Feelings of radical alienation and disconnection from the surroundings and from other human beings, that have become an inevitable part of modern urban life, find a potent expression in his films and specially in the face of Monica Vitti and Jeanne Moreau. His films are a critique of the idea of modernity and document the costs of material prosperity in terms of wasted human lives and potential for genuine happiness and fulfillment. The most common symbol he chooses to show this is that of modern architecture. All those empty buildings, which in their weird geometric shapes, just seem to be completely devoid of any human element whatsoever. As if the world itself is trying to reject humanity. The same is for the emptied streets on which Monica Vitti spends most of the time just walking aimlessly. It's the streets and roads which have deserted human beings, not the other way round.

People looking for narrative closure and clean-cut explanations for character behavior will be disappointed with his films. What is important there, is the "mood", which Antonioni creates and sustains by employing very stylish camera work and scene compositions. And through this he explores the ideas in a purely visual manner. But what exactly are those ideas? Feelings of radical alienation and disconnection from the surroundings and from other human beings, that have become an inevitable part of modern urban life, find a potent expression in his films and specially in the face of Monica Vitti and Jeanne Moreau. His films are a critique of the idea of modernity and document the costs of material prosperity in terms of wasted human lives and potential for genuine happiness and fulfillment. The most common symbol he chooses to show this is that of modern architecture. All those empty buildings, which in their weird geometric shapes, just seem to be completely devoid of any human element whatsoever. As if the world itself is trying to reject humanity. The same is for the emptied streets on which Monica Vitti spends most of the time just walking aimlessly. It's the streets and roads which have deserted human beings, not the other way round.

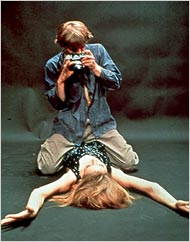

Third, his concern with the mise-en-scene and scene composition. Antonioni was perhaps the most stylish filmmaker of his generation. What is most remarkable is how he composes his scenes specially how he chooses what to put in background and what in foreground. Normally, in a scene the protagonist will occupy the centre of the frame and the entire focus will be on him with the background there only to supply the context, or as in Hollywood films, to make the scene look "beautiful" (in the most cliched way of course). In Antonioni's films the background is a character in itself, sometimes even more important than the protagonists in front of them. For example, in that brilliant island sequence of L'Avventura, it is that landscape which occupies most of the frame, with the characters there only in corners, or else, shot in such long shots as to make their personality relatively unimportant as compared to those landscapes. It creates a weird disorienting effect in the viewer. Also remarkable is the scene where Claudia and Sandro make love in an open field. It is shot in such an unconventional style, that just by watching the sex scene, you get the idea that it is an empty sexual connection, one that is not going to last.

Fourth, cinema of absence. What troubles many people when watching these films is why do the characters just walk and walk on those empty streets? Why are the buildings always vacant? And in general, why is there so much of open space everywhere? I think it is a very radical idea, the idea that you can comment on something by NOT showing something where it was expected. It is in this context that the brilliant ending of L'Eclisse makes sense.  The two lovers in the end promise to meet once again to continue their affair but looking at their faces and the way they utter those words, it becomes clear that it is an empty promise after all. What follows is a long (seven minutes) sequence of silent shots of the place and its neighbourhood where they were supposed to meet. It is by the emptiness in those spaces that we find out that the spark of love has indeed died and that it is truly THE END in every sense of the term. The final scene is that of a street lamp which resembles an eclipse, perhaps signifying an apocalypse or the end of the world itself.

The two lovers in the end promise to meet once again to continue their affair but looking at their faces and the way they utter those words, it becomes clear that it is an empty promise after all. What follows is a long (seven minutes) sequence of silent shots of the place and its neighbourhood where they were supposed to meet. It is by the emptiness in those spaces that we find out that the spark of love has indeed died and that it is truly THE END in every sense of the term. The final scene is that of a street lamp which resembles an eclipse, perhaps signifying an apocalypse or the end of the world itself.

Fifth, cinema of silence. There is a general tendency in people that when there is no sound coming from the screen they shut down their sensory perceptions. That's the reason why background score is so ubiquitous in Hollywood movies, or for that matter any cinema which relies solely on "action". In contrast, Antonioni's cinema is a cinema of thoughts, moods and ideas. What makes these films even more masterful is that Antonioni relies solely on visual style. Dialogues can never get you inside the head of the character, specially when the characters in question are feeling alienated, that's why there are so many silent scenes and even when someone speaks something it does nothing to propel the plot forward. So on the surface you get the feeling that "nothing is happening" but it is inside the head of those characters that things are happening which is like it is in the real world too.

Sixth, the impossibility of love in the modern world. These three films are some of the most eloquent essays on the phenomenon of the breakdown in human relationships, specially in the advanced and modern societies. What makes these films so disquieting and despairing is that Antonioni doesn't treat it as a problem which has anything to do with the individuals in question but rather treats it just as a symptom, a symbol signifying a far deeper malaise in the society. It is in this context that the final reconciliatory scene (or is it?) in L'Avventura makes sense. In modern societies we have done away with the moorings of tradition, family, religion or community but haven't replaced them with anything substantial. Eros in itself isn't powerful enough a force to keep people together, that's what Antonioni suggests. In a remarkable scene in L'Eclisse towards the end, sensing that her relationship with her stockbroker boyfriend is going to end Vittoria says, "I wished I didn't love you or I loved you much more". It is this uncertainty towards everything which has crept in our consciousness, because we have forsaken the certainties, false of course, of religion or tradition, that is creating havoc in our lives, ultimately leading to unhappiness, ennui and anxiety.

In modern societies we have done away with the moorings of tradition, family, religion or community but haven't replaced them with anything substantial. Eros in itself isn't powerful enough a force to keep people together, that's what Antonioni suggests. In a remarkable scene in L'Eclisse towards the end, sensing that her relationship with her stockbroker boyfriend is going to end Vittoria says, "I wished I didn't love you or I loved you much more". It is this uncertainty towards everything which has crept in our consciousness, because we have forsaken the certainties, false of course, of religion or tradition, that is creating havoc in our lives, ultimately leading to unhappiness, ennui and anxiety.

Finally Antonioni's influence. Antonioni was easily the most stylish and radically innovative filmmakers of his generation and it his style and thematic questions that concern most of the great filmmakers currently working, specially those exploring the phenomenon of alienation and urban isolation and dislocation like Michael Haneke, Wong Kar-wai, Tsai Ming-liang and others. They all trace their pedigree to Antonioni. He has been responsible for freeing narrative cinema from the pre-modern shackles of conventional storytelling and brought cinema back to the level of literature (well, almost) of its time.

Anyway if you are in New York, don't miss the Antonioni retrospective which is on at the BAM cinematheque all this week. Details here. I can only imagine what kind of experience it would be to watch L'avventura on the big screen for the first time. I had earlier linked to the articles about the retrospective in NYT and Village Voice.

I had earlier written a post on L'Eclisse. You can find it here.

11 comments:

Ah! Have to come back and read this one carefully. :)

post of stellar proportions, im awed at your grasp of this subject, both antonioni and alienation, this misunderstood spiritual malady surrouding us all, i rem listening to the audio commentary on the l'aventurra dvd, a year back, never paid much attention, i need a re-listen, thanks.

every filmmaker(in my knowledge) who deals with alienation in his cinema, does a phenomenal job, and this 'alienation' is not thematic, its in the very soul, the fabric, the mood of the film, foreboding, you can feel it in your innards, all of them, it must be the thing we are all built of.

Alok, excellent post, written with the kind of passion one would expect when you’re talking about something you feel really strongly about. I enjoy Antonioni’s work too (obviously not to the same extent as you) – but then, you know how catholic my tastes are :)

But I’d like to address one of the points you’ve made (and don’t take this as a criticism of Antonioni or of others who approached filmmaking the way he did) – your undermining of narrative cinema, which is based on straightforward storytelling. The fact is, the embedding of ideas and themes within the framework of a “straight story” can be a more difficult and complex process than “exploring ideas in a direct manner”. Some of the classical Hollywood filmmakers from the pre-modern period, eg John Ford, William Wyler, Howard Hawks etc dealt with some very strong ideas in their films – and those shouldn’t be ignored just because the moviemaking style was narrative-based (or because some of it seems sloppy and sentimental today, which after all is an inevitable result of our “post-modern” self-consciousness).

Conversely, it’s possible to argue that some of the directors who get extolled as “artists with Ideas” actually take the easy way out by concentrating on idea-presentation/symbolism at the expense of a story.

Unrelated: I don’t really understand what you mean by “bringing cinema back to the level of literature (well, almost) of its time”. Those are two completely different mediums, and this attitude – that cinema is intrinsically inferior and that it needs to become some sort of visual equivalent to literature – is responsible for a lot of the sneering, condescending film criticism one sees these days. Like Robin Wood says in the prologue to his Hitchcock book, “If we were yet able to appreciate cinema on its own terms instead of mentally reducing it to literature, we would be able to see the artistry of Hitchcock’s films”. (I’d include a few other directors in that list – Brian DePalma for one – whose films don’t ostensibly deal with very profound ideas but which can be very powerful and thought-provoking nonetheless.)

In fact, in your post you talk about Antonioni’s great visual quality as well as the cinema of silence and the cinema of absence. Those are the qualities of a medium that operates on very different principles from literature – so why compare the two?

An even more important reason to like Antonioni: The Yardbirds!

Just kidding. Terrific post.

I am so tempted to head over to BAM this weekend....

v, thanks...I didn't think it was that long though :)

madhur, "stellar proportions"? come on ;)

Yes, it is strange how common this theme of alienation has become, specially in contemporary art-house cinema, which is understandable because it is such a common and widespread feeling, almost like a part of the zeitgeist, a way of life even.

km, Yardbirds? Hmmm. I don't exactly remember the song though. Will have to see blowup again.

Jai, thanks! I was actually comparing the progress or evolution of form in literature vis-a-vis that in cinema. I agree, they both have their own language and rules of grammar and it is not fruitful to compare the two using some common ground.

At the turn of century literature moved away from the character driven storytelling because people realized that it was naive to assume that a few strokes of wordplay describing actions can capture an individual consciousness in its totality or that a character behavior can be explained using models of cause and effect. Conventional storytelling also left little scope for exploring subjectivity. Conventional realism of course has its own successes but all the new experimentation opened new doors for writers to explore things which they never thought possible. It was in this context that I said that antonioni and others like him did the same for cinema and brought a similar modernism in cinema too.

Also I didn't want to undermine narrative cinema. I like those movies of golden age hollywood too, (though I will name Huston and Wilder as my favourites.) Those film noirs for example, contain some of the best examples of alienated heroes! It is just that Antonioni and others like him showed that it was possible to free yourself for limitations of narrative and that doing it opens interesting new grounds for cinema as an artistic medium.

Nicely written, Alok. I havent seen L'Eclisse or La Notte. But I will need to rectify that pretty soon.

Thanks.

Alok, thanks a lot for the post. I will see La Notte soon.

thank you vb and anurag! :)

'Tis 5 in the AM and I find myself perusing through the contents of this sterling little blog of yours.

Consider yourself successful in garnering yet another idler to fancy your musings.

sterling blog.. ummm... thank you :)

Post a Comment