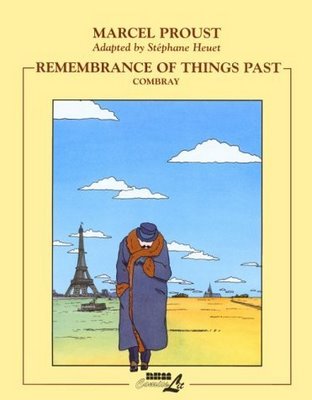

Thomas Bernhard: Wittgenstein's Nephew

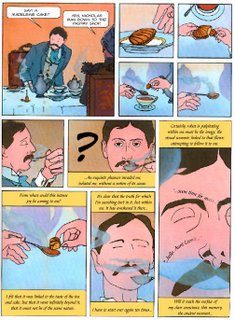

Wittgenstein's Nephew is an autobiographical short novel by the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard. I had first heard of him in one of the articles about the late German writer and one of my literary idols W G Sebald. Sebald considered him as an influence on his own writing although now after having read Wittgenstein's Nephew I can't imagine what could that influence be. They both share a deeply pessimistic worldview alright (like all Germanic writers I guess) but the sameness ends there (as far as I can extrapolate from reading this single book.) Sebald's melancholy resignation and a deep empathetic understanding of the human condition and the mysterious workings of the universe (Yes!) is replaced by a bitter and bilious fury in Bernhard. Their prose styles also couldn't be more different. Sebald's prose is classical and controlled while Bernhard believes in the sledgehammer approach, he drives home his point of view by repetition and rhetoric and the sheer fury of his anger and bitterness doesn't leave any room for any Sebaldian meditation or reflection. Bernhard also has little tolerance for cliches (not that Sebald is fond of them but he manages to avoid them completely) and one of the pleasures of reading Wittgenstein's Nephew is the way he makes fun of cliches by using them deliberately. Often many words and phrases are shown in italics or prefixed by qualifiers like "so-called" ("it was there that our friendship deepened".) The novel is about the author-narrator's real life friendship with Paul Wittgenstein, the nephew of the famous philosopher of logic and language. Paul struggled with periodic bouts of madness and the author struggled with his lung disease throughout his life. In real life also Bernhard spent a couple of years in a sanatorium. Most of the book is about what Bernhard thinks of disease, both physical and mental. At one place in the book he divides the humanity into two mutually hostile and irreconcilable groups -- that of the healthy and the other of the sick. "The healthy never had the patience with the sick, nor, of course the sick ever had the patience with the healthy. This fact must not be forgotten."

The novel is about the author-narrator's real life friendship with Paul Wittgenstein, the nephew of the famous philosopher of logic and language. Paul struggled with periodic bouts of madness and the author struggled with his lung disease throughout his life. In real life also Bernhard spent a couple of years in a sanatorium. Most of the book is about what Bernhard thinks of disease, both physical and mental. At one place in the book he divides the humanity into two mutually hostile and irreconcilable groups -- that of the healthy and the other of the sick. "The healthy never had the patience with the sick, nor, of course the sick ever had the patience with the healthy. This fact must not be forgotten."

He also gives some background about the life of Paul who, at least the author claims, was a distinguished thinker in his own right. Also, I didn't know that the Wittgenstein family was one of the richest in Vienna. And Paul like his illustrious uncle donated most of his fortune to others and himself led a life of penury and supported himself with the generosity of his relatives. Also the wiki article says, "His [Ludwig's] family also had a history of intense self-criticism, to the point of depression and suicidal tendencies. Three of his four brothers committed suicide." And actually it is this self-criticism that is I think the central subject of the book alongwith the madness that results from it.

What is most strange about the book is that often sympathetic accounts of his friend's illness are punctuated by author's own rants against, well, basically everything. This is the author railing against nature:

I know nothing about nature. I hate nature, because it is killing me. I live in the country only because the doctors have told me that I must live in the country if I want to survive--for no other reason. In fact I love everything except nature, which I find sinister; I have become familiar with the malignity and implacability of nature through the way it has dealt with my body and soul, and being unable to contemplate the beauties of nature without at the same time contemplating its malignity and implacability, I fear it and avoid it whenever I can.

He doesn't think of doctors, specially those in the psychiatry profession very highly too:

Like all other doctors, those who treated Paul continually entrenched themselves behind Latin terms, which in due course they built up into an insuperable and impenetrable fortification between themselves and the patient, as their predecessors had done for centuries, solely in order to conceal incompetence and cloak their charlatanry. From the very start of their treatment, which is known to employ the most inhuman, murderous, and deadly methods, Latin is set up as an invisible but uniquely impenetrable wall between themselves and their victims. Of all medical practitioners, psychiatrists are the most incompetent, having a closer affinity to the sex killers than to their science.

He then says that all his life he has "dreaded nothing so much as falling into their hands" and that they are "a law unto themselves." He reserves even more bitter and angry words for the Austrian government and the official literary establishment.

Accepting a prize is in itself an act of perversity, my friend told me at the time, but accepting a state prize is the greatest.In real life also Bernhard is famous as a "nest-fouler" in his native country and had forbade the staging of all his plays in Austria in his will. He despises the Austrian theatre management, the Austrian actors, directors who mangle his plays. Surprisingly he praises the Swiss-German actor Bruno Ganz (Wings of Desire, Downfall) very highly. He says this after the theatre management refused to hire Ganz for the production of one of his plays:

Their opposition was prompted not only by existential dread, as it were, but by existential envy, for Bruno Ganz, a towering theatrical genius and the greatest actor Switzerland has ever produced, inspired the ensemble with what I would describe as the fear of artistic death. It still strikes me as a sad and sickening piece of perversity, and an episode in Viennese theater history too disgraceful to be lived down, that the actors of the Burgtheater should have attempted to prevent the appearance of Bruno Ganz, going so far as to draw up a written resolution and threaten the management, and that the attempt should have actually succeeded. For as long as the Viennese theater has existed, decisions have been made not by the theater director but by the actors. The theater director has no say, least of all at the Burgtheater, where all the decisions are made by the matinee idols, who can be unhesitatingly described as feebleminded -- on the one hand because they have no understanding of the theatrical art and on the other hand because they quite brazenly prostitute the theater, both to its own detriment and to that of the public -- though it has to be added that for decades, if not for centuries, the public has been prepared to put up with these Burgtheater prostitutes and allowed them to dish up the worst theater in the world.

He hates coffee-houses and the literary people who go there. Not surprisingly he likes reading Schopenhauer, perhaps the gloomiest philosopher who ever lived. In the end he movingly, though still maintaining his highly anti-sentimental tone, describes the last days of his friend and then cruelly narrates how he shunned his friend like everyone else during his last days because he was "afraid of a direct confrontation with death." He then says:

I had traced his dying over over a period of more than twelve years. And I had used Paul's dying for my own advantage, exploiting it for all I was worth. It seems to me that I was basically nothing but the twelve-year witness of his dying, who drew from his friend's dying much of the strength he needed for his own survival. It is not farfetched to say that this friend had to die in order to make my life more bearable and even, for long periods, possible.

Bernhard's bitter pessismism is curiously very entertaining and very addictive. Personally also I feel that if you can't drive away melancholy, at least be bitter and pissed off with everything. It is much better than Sebaldian passive resignation which is much more destructive and useless. Unfortunately these days I am in the Sebaldian mode, and even reading it didn't change my mental state. Anyway read it and decide for yourself.

And finally thanks to cheshire cat for recommending me the book! This looks like a nice site about his life and works.