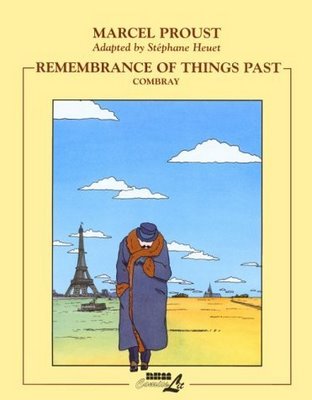

Proust: The Comic Book!

When the comic book adaptation of Proust's novel was published in France a few years ago, the literary establishment was predictably scandalized and horrified. Will the popular culture industry not leave even Proust alone? Will even Proust be commodified and sold in the market? Is the war between art and commerce over, as we are led to believe, and as all evidences from the popular culture prove? They must have wondered.  Well, I think they needn't have worried. Having "read" it (isn't it interesting, how we don't have a word for what we "do" with a comic book), I find it positively harmless, even amusing at a lot of places, and I am saying this as a dedicated Proustian and an enthusiastic member of the Proust cult, though still mostly a newbie. It is not one of those illustrated classics, meant to entice children and young people, who like Lewis Caroll's Alice, don't like reading books which don't have images. In any case I don't think young people or people who always feel "young at heart" will ever appreciate Proust's message. They will find the novel, and even this comic book, long winded and pointless whining of someone who just had a lot of free time. Same for the readers of Proust too ("you don't have anything else to do? any thing else?"). You have to be past a certain age or at least you should see the world as a (truly) middle-aged man would, to "get" what Proust is really trying to say.

Well, I think they needn't have worried. Having "read" it (isn't it interesting, how we don't have a word for what we "do" with a comic book), I find it positively harmless, even amusing at a lot of places, and I am saying this as a dedicated Proustian and an enthusiastic member of the Proust cult, though still mostly a newbie. It is not one of those illustrated classics, meant to entice children and young people, who like Lewis Caroll's Alice, don't like reading books which don't have images. In any case I don't think young people or people who always feel "young at heart" will ever appreciate Proust's message. They will find the novel, and even this comic book, long winded and pointless whining of someone who just had a lot of free time. Same for the readers of Proust too ("you don't have anything else to do? any thing else?"). You have to be past a certain age or at least you should see the world as a (truly) middle-aged man would, to "get" what Proust is really trying to say.

Now coming back to the book, I think a visual interpretation of Proust's novel is an excellent idea because though the book is mainly concerned with "the invisible", the "internal" life, the life of the mind and the flickering of individual consciousness under the effect of the external, material world, the novel is also a grand social  comedy, populated by grotesque and lively characters and filled to brim with events and scenes. In fact long sections of the novel are devoted to painstaking descriptions of parties, social gatherings, the way people dress, behave and talk. In other words it is just like any other "realistic" nineteenth century novel. In fact Proust mentions Balzac and his collection of novels under the "human comedy" as an inspiration to the structure of his novel.

comedy, populated by grotesque and lively characters and filled to brim with events and scenes. In fact long sections of the novel are devoted to painstaking descriptions of parties, social gatherings, the way people dress, behave and talk. In other words it is just like any other "realistic" nineteenth century novel. In fact Proust mentions Balzac and his collection of novels under the "human comedy" as an inspiration to the structure of his novel.

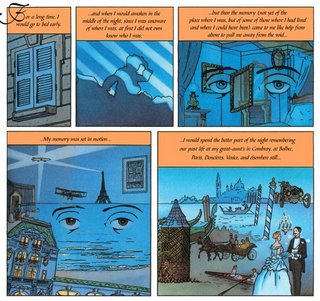

Now the sketches in this comic book are just like in any other comic book -- in other words they are cartoonish. There are not many lines on the faces and yet the author/illustrator somehow captures the feelings and gives those figures some complexity. It is specially visible in the sketch of the narrator as the little kid when he agonizes over his mother's kiss before going to sleep. Two dots for an eye, a hint of a nose and another dot for mouth, that's all, and yet you can feel his anguish. Was it because I had read the novel first and also because it is one of my favourite passages? I don't know, I can't say. Perhaps some Proust virgin might answer it more honestly.

The prose inside the balloons and descriptions are close approximations of the original, though it goes without saying that the author covers a very small ground as compared to the original. The book is around eighty pages while the "combray" chapter in the novel runs to almost three hundred pages. Still I think reading it is very evocative. Take a look at the following excerpts from the comic book and the original. Again it is one of the my favourite passages so I don't know if it can work in isolation. (I don't really know if it is meant to be read on its own or not.) The narrator is describing how the sight of a church steeple or similar shape in any remote town reminds him of the church steeple of Combray where he spent his childhood.

...whenever, in a large, provincial city or in a quarter of Paris I do not know well,

a passerby shows me in the distance this hospital belfry, or that steeple as a reference point....

However little my memory can find some obscure resemblance to that dear and vanished shape....

...immobile, trying to remember, feeling submerged within me lands conquered anew from the forgotten, drying out and rising up...

...I seek my path again.

I turn on to a street...

...but...it is within my heart...

These lines are separated by different images in the comic book. It shows through some kind of cinematic dissolve the narrator being transported back to his childhood and from where the story continues.

This is the original paragraph in the Scott Moncrieff translation:

And so even to-day in any large provincial town, or in a quarter of Paris which I do not know well, if a passer-by who is ‘putting me on the right road’ shews me from afar, as a point to aim at, some belfry of a hospital, or a convent steeple lifting the peak of its ecclesiastical cap at the corner of the street which I am to take, my memory need only find in it some dim resemblance to that dear and vanished outline, and the passer-by, should he turn round to make sure that I have not gone astray, would see me, to his astonishment, oblivious of the walk that I had planned to take or the place where I was obliged to call, standing still on the spot, before that steeple, for hours on end, motionless, trying to remember, feeling deep within myself a tract of soil reclaimed from the waters of Lethe slowly drying until the buildings rise on it again; and then no doubt, and then more uneasily than when, just now, I asked him for a direction, I will seek my way again, I will turn a corner... but... the goal is in my heart...

Proust is generally famous for his philosophy of how time and duration are experienced by us and how past is never really past because it is always bleeding into the present, by unexpected means through the faculty of involuntary memory, but in this passage (I have only excerpted a very small portion), and at many places elsewhere in the novel, he shows how our experiences of space and material objects are also subjective, how we are constantly negotiating our own relationship with the material world around us through our perception and that relationship is completely personal and defined completely by solitary and unique individual experience. The more attached you are to the world around you, the unique the experience will be. Of course, the narrator is at the extreme of sensitivity and attachment. He finds himself painfully attached to even the church steeple. He is always defining the streets, locations, houses, trees etc relative to his beloved steeple which is his, and only his, point of reference for everything around him. His experience of space is purely his, he can't share it with anyone else. Reading the passage in the comic book obviously won't doesn't say about all this and more. But perhaps it does give some hint. The publisher's page also previews images (excerpted above) from other famous scenes from the chapter. One in the beginning where the narrator muses philosophically on sleep, forgetting and self-knowledge and the other, the famous madeleine scene.

Overall as I said in the beginning, the book is quite harmless and any gloomy prognostications about the demise of art based on its existence are completely misplaced. Having said that, I am not too excited about reading the other volumes.

p.s I had written earlier about the movie adaptation of the last volume Time Regained too here.

4 comments:

Hi Alok

well, I consider self a virgin to Proust philosophy, but did read others who carry a shade of his philosophy. I paused at your space and it's been wonderful an experience as you gently took the hand of the reader into the journey of Proust...just my observation on

the "Comic/Convenient" version of regular literature....I feel, the latter gives me a lot more space to move around, mobilise my imagination and run along with the writer or the narrator. Sure the former tickles the child in me, somehow, I sense the absence of depth and the involvement. well, this is my opinion. but a comical rendition of a classic ceratinly takes the work to a much larger audience...

Loved your space a lot...what you'd spread over is used to be my kind of reading, which somehow remained uncared for in my life...but am reviving it..

can see Flaubert n Madame Bovary down the page..will come to that soon,as he is amongst my fav classic writers...thank you. Jyo

thanks a lot! you have made my day. I always fear that I am blabbering some pompous nonsense :)

About your comment, I liked this book quite a lot and I am sure anybody who reads abridged or interpretational versions will understand that they can never replace the original. And it does work as a good introduction in most cases, as you point out.

I haven't read Proust fully myself yet and I am still trying and discovering.

Dont want to sound like a purist, but I find it difficult to understand how a writer like Proust can be rendered into a comic book- the situation itself sounds comical, if you permit.

Creating a comic involves a certain degree of reductionism and linearity, while the purpose of a writer like Proust is precisly to introduce elements of ambiguity, of time, space and is closer to say, impressionism or other such schools of painting rather than to comic books.

You are of course right, a straight-forward adaptation is pointless and even the most artistic of illustrator can only touch the tip and barely approximate the original.

But having said that, I thought it was an admirable experiment and I do think it is possible to create that vivid impressionistic sense of going-beyond-Time that Proust manages to do in his prose in a visual medium. The movie I link to in the end in an earlier post of mine is an extremely complex adaptation for example.

After all, there are many different narrative media. People can take up the challenge and try to replicate the same in other media. It's a challenge that people can take up. The trailer for the movie time regained ffor example says, it's "the holy grail of Proustian cinema"

Post a Comment