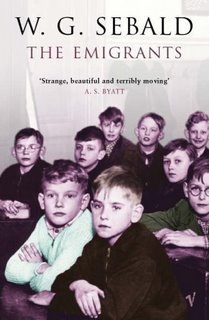

The Emigrants is the best book of fiction that I have read this year so far (I read it in January). I felt hopelessly incapable to write anything about it so I am reproducing a review by Cynthia Ozick first published in The New Republic. It is not freely available on the internet and don't ask me how I got access to new republic archives.

The Emigrants

by W. G. Sebald

translated by Michael Hulse

(New Directions, 237 pp., $22.95)

There is almost no clarifying publisher's apparatus surrounding W. G. Sebald's restless, melancholy and (I am almost sorry to say) sublime narrative quartet. One is compelled--

There is almost no clarifying publisher's apparatus surrounding W. G. Sebald's restless, melancholy and (I am almost sorry to say) sublime narrative quartet. One is compelled--

ludicrously, clumsily--to settle for that hapless term, what is a "narrative quartet'?) because the very identity of this work remains murky. Which parts of it are memoir, which fiction--and ought it to matter? As external facticity, we learn from the copyright page that the date of the original German publication is 1993, and that the initials W.G. represent Winfried Georg. A meager paragraph supplies a handful of biographical notes: the author was born in Wertach im Allgau, Germany; he studied German language and literature in Freiburg (where, one recalls, Heidegger's influence as rector of the university, despite his earlier Nazi affiliations, extended well into the 1970s), and later in Francophone Switzerland and in Manchester, England, where he began a career in British university teaching. Two dates standout: Sebald's birth in 1944, an appalling year for all of Europe, and for European Jews a death's-head year; and 1970, when, at the age of 26, Sebald left his native Germany and moved permanently to England.

It cannot be inappropriate to speculate why. One can imagine that in 1966, during the high period of Germany's "economic miracle," when Sebald was (as that meagerly informative paragraph tells us) a very young assistant lecturer at the University of Manchester, he may have encountered a romantic attachment that finally lured him back to Britain; or else he came to the explicit determination, with or without any romantic attachment (yet he may, in fact, have fallen in love with the pathos of soot-blackened Manchester), that he would anyhow avoid the life of a contemporary German. The life of a contemporary German: I observe, though from a non-visitor's distance, and at so great a remove now from those twelve years of intoxicated popular zeal for Nazism, that such a life is somehow still touched with a smudge, or taint, of the old shameful history; and that the smudge, or taint--or call it, rather, the little tic of self-consciousness--is there all the same, whether it is regretted or repudiated, examined or ignored, forgotten or relegated to a principled indifference. Even the youngest Germans traveling abroad, especially in New York, know what it is to be made to face, willy-nilly, a history of national crime, however long receded and repented.

For a German citizen to live with 1944 as a birth date is reminder enough. Mengele stood that year on the ramp at Auschwitz, lifting the omnipotent gloved hand that dissolved Jewish families: mothers, babies and the old to the chimneys, the rest to the slave labor that temporarily forestalled death. Ah, and it is sentences like this last one that present-day Germans, thriving in a democratic Western polity, resent and decry. A German professor of comparative literature accused me not long ago--thanks to a sentence like that--of having a fossilized mind, of being unable to recognize that a nation "develops and moves on." Max Ferber, the painter-protagonist of the final tale in Sebald's quartet, might also earn that professor's fury. "To me, you see," Sebald quotes Ferber, "Germany is a country frozen in the past, destroyed, a curiously extraterritorial place." It is just this extraterritorialism--this ineradicable, inescapable, ever-recurring, hideously retrievable 1944--that Sebald investigates, though veiled and at a slant, in The Emigrants. And it was, I suspect, not the democratic Germany of the economic miracle from which Sebald emigrated in 1970; it may have been, after all, the horribly frozen year of his birth that he meant to leave behind.

That he did not relinquish his native language or its literature goes without saying; and we are indebted to Michael Hulse, Sebald's translator (himself a poet), for allowing us to see, through the stained glass of his consummate Englishing, what must surely be the most delicately powerful German prose since Thomas Mann. Or, on second thought, perhaps not Mann really, despite a common attraction to the history-soaked. Mann on occasion can be as heavily ornate as those carved mahogany sideboards and wardrobes--vestiges of proper German domesticity abandoned by the fleeing Jews-- which are currently reported to add a certain glamorous middle-'30s tone to today's fashionable Berlin apartments. Sebald is more translucent than Mann. He writes as Turner paints: "To the south, lofty Mount Spathi, two thousand metres high, towered above the plateau, like a mirage beyond the flood of light. The fields of potatoes and vegetables across the broad valley floor, the orchards and clumps of other trees, and the untilled land, were awash with green upon green, studded with the hundreds of white sails of wind pumps." Notably, this is not a landscape viewed by a fresh and naked eye. It is, in fact, a verbal rendering of an old photograph--a slide shown by a projector on a screen.

An obsession with old photographs is what separates Se-bald from traces of Mann, from Turner's hallucinatory mists, from the winding reflections of Proust (with whom, in his freely searching musings and paragraphs wheeling cumulatively over pages, Sebald has been rightly compared), and even from the elusively reappearing shade of Nabokov. The four narratives recounted in The Emigrants are each accompanied by superannuated poses captured by obsolete cameras; in their fierce time-bound isolations they suggest nothing so much as Diane Arbus. And, wittingly or not, Sebald evokes Henry James as well, partly for his theme of expatriation, and partly on account of the mysterious stillness inherent in photography's icy precision. In the late New York edition of his work, James eschewed illustration, that nineteenth-century standby, and turned instead to the unsentimental fixity of photography's Time and Place, or Place-in-Time. In Sebald's choosing to incorporate so many photos (I count eighty-six in 237 pages of text)-- houses, streets, cars, headstones, cobblestones, motionless schoolchildren, mountain crevasses, country roads, posters, roofs, steeples, hotel postcards, bridges, tenements, grand and simple rooms, overgrown gardens--he, like James with his 1909 frontispieces, is acknowledging the uncanny ache that cries out from the silence of solid things. These odd old pictures attach to Sebald's voice like an echo that cannot be heard, no matter how hard one strains; they lie in the crevices of print with a terrible helplessness, deaf-mutes without the capacity to sign.

The heard language of these four stories--memories personal, borrowed, invented-- is, as I noted earlier, sublime; and I wish it were not, or, if that is not altogether true, I admit to being disconcerted by a grieving that has been made beautiful. Grief, absence, loss, longing, wandering, exile, homesickness: these have been made millennially, sadly beautiful since the Odyssey, since the Aeneid, since Dante ("You shall come to know how salt is the taste of another's bread"); and, more venerably still, since the Psalmist's song by the waters of Babylon. Nostalgia is itself a lovely and piercing word, and even more so is the German Heimweh, "home-ache." It is art's sacred ancient trick to beautify pain, to romanticize the shadows of the irretrievable. "O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again": Thomas Wolfe, too much scorned for boyishness, tolls that bell as mournfully as anyone; but it is an American tolling, not a German one.

Sebald's mourning bell is German, unmistakably German; when it tolls the hour, it is almost always 1944. And if I regret the bittersweet sublime Turner-like wash of Beauty that shimmers over the whole of this volume, it is because sublime grieving is a category of yearning, fit for that which is irretrievable. But 1944 is always, always retrievable. There stands Mengele on the ramp, forever lifting his gloved hand; and there, sent off to the left and the right, are the Jews, going to the left and the right forever. Nor is this any intimation of Keats's urn--there are human ashes in it. The posthumous sublime is discordant; an oxymoron. Adorno told us this long ago: after Auschwitz, no more poetry. We resist such a dictum; the Psalmist by the waters of Babylon resisted it; Paul Celan resisted it; Sebald resists it. It is perhaps natural to resist it.

So, in language sublime, Sebald is haunted by Jewish ghosts--Europe's phantoms: the absent Jews, the deported, the gassed, the suffering, the hidden, the fled. There is a not-to-be-overlooked irony (a fossilized irony, my professor-critic might call it) in Sebald's having been awarded the Berlin Literature Prize--Berlin, the native city of Getshorn (ne Gerhardt) Scholem, who wrote definitively about the one-sided infatuation of Jews in love with high German culture and with the Vaterland itself. The Jewish passion for Germany was never reciprocated--until now. Sebald returns that Jewish attachment, although tragically: he is too late for reciprocity. The Jews for whom he searches are either stricken escapees or smoke. Like all ghosts, they need to be conjured.

Or, if not conjured, then come upon by degrees, gradually, incrementally, in rots and echoes. Sebald allows himself to discover his ghosts almost stealthily, with a dawning notion of who they really are. It is as if he is intruding on them, and so he is cautious, gentle, wavering at the outer margins of the strange places in which he finds them. In "Dr. Henry Selwyn," as the first narrative is called, the young Sebald and his wife drive out into the English countryside to rent a flat in a wing of an overgrown mansion surrounded by a neglected garden and a park of looming trees. The house seems deserted. Tentatively, they venture onto the grounds and stumble unexpectedly on a white-haired, talkative old man who describes himself as "a dweller in the garden, a kind of ornamental hermit." By the time we arrive at the end of this faintly Gothic episode, however, we have learned that Dr. Henry Selwyn was once a cheder-yingl, a Jewish schoolchild named Hersch Seweryn in a village near Grodno in Lithuania.

When he was 7 years old his family, including his sisters Gita and Raja, set out for America, like thousands of other impoverished shtetl Jews at the beginning of the century; but "in fact, as we learnt some time later to our dismay (the ship having long since cast off again), we had gone ashore in London." The boy begins his English education in Whitechapel in the Jewish East End and eventually wins a scholarship to Cambridge to study medicine. Then, like a proper member of his adopted milieu, he heads for the Continent for advanced training, where he becomes--again like a proper Englishman-- enamored of a Swiss Alpine guide named Johannes Naegeli. Naegeli tumbles into a crevasse and is killed; Selwyn returns home to serve in the Great War and in India. Later he marries a Swiss heiress who owns houses in England and lets flats. He has now completed the trajectory from Hersch Seweryn to Dr. Henry Selwyn. But one day, when the word "homesick" flies up out of a melancholy conversation with Sebald, Selwyn tells the story of his childhood as a Jewish immigrant.

The American term is immigrant, not emigrant, and for good reason, America being the famous recipient of newcomers: more come in than ever go out. Our expatriates tend to be artists, often writers: hence that illustrious row of highly polished runaways, James, Eliot, Pound, Wharton, Stein, Hemingway. But an expatriate, a willing (sometimes temporary) seeker, is not yet an emigrant. And an emigrant is not a refugee. A cheder-yingl from a shtetl near Grodno in a place and period not kind to Jews is likely to feel himself closer to being a refugee than an emigrant: our familiar steerage image expresses it best. Sebald, of course, knows this and introduces Dr. Selwyn as a type of foreshadowing. Displaced and homesick in old age for the child he once was (or in despair over the man he has become), Dr. Selwyn commits suicide. And on a visit to Switzerland in 1986, Sebald reads in a Lausanne newspaper that Johannes Naegeli's body has been found frozen in a glacier seventy-two years after his fall. "And so they are ever returning to us, the dead," Sebald writes.

But of exactly what is Dr. Selwyn a foreshadowing? Sebald's second narrative, titled "Paul Bereyter," is a portrait of a German primary school teacher Sebald's own teacher in the '50s, "who spent at least a quarter of all his lessons on teaching us things that were not on the syllabus." Original, inventive, a lover of music, a scorner of catechism and priests, an explorer, a whistler, a walker ("the very image ... of the German Wandervogel hiking movement, which must have had a lasting influence on him from his youth"), Paul Bereyter is nevertheless a lonely and increasingly aberrant figure. In the '30s he had come out of a teachers' training college (here a grim photo of the solemn graduates, in their school ties and rather silly caps) and taught school until 1935, when he was dismissed for being a quarter-Jew.

The next year his father, who owned a small department store, died in a mood of anguish over Nazi pogroms in his native Gunzenhausen, where there had been a thriving Jewish population. After the elder Bereyter's death, the business was confiscated; his widow succumbed to depression and a fatal deterioration. Paul's sweetheart, who had journeyed from Vienna to visit him just before he took up his first teaching post, was also lost to him: deported, it was presumed afterward, to Theresienstadt. Stripped of father, mother, inheritance, work and love, Paul fled to tutor in France for a time, but in 1939 drifted back to Germany, where, though only three-quarters Aryan, he was unaccountably conscripted. For six years he served in the motorized artillery all over Nazi-occupied Europe. At the war's end he returned to teach village boys, one of whom was Sebald.

As Sebald slowly elicits his old teacher's footprints from interviews, reconstructed hints and the flickering lantern of his own searching language, Paul Bereyter turns out to be that rare and mysterious figure: an interior refugee (and this despite his part in the German military machine)-- or call it, in ominous '30s lingo, an internal emigrant. After giving up teaching--the boys he had once felt affection for he now began to see as "contemptible and repulsive creatures"--he both lived in and departed from German society, inevitably drawn back to it, and just as inevitably repelled.

All his adult life, Sebald discovers, Paul Bereyter had been interested in railways. (The text is now interrupted by what appears to be Paul's own sketch of the local Bahnhof, or station, with the inscription "So ist es seit dem 4.10.1949," "This is how it has looked since April 10, 1949.") On the blackboard he draws "stations, tracks, goods depots, and signal boxes" for the boys to reproduce in their notebooks. He keeps a model train set on a card table in his fiat. He obsesses about timetables. Later, though his eyesight is troubled by cataracts, he reads demonically--almost exclusively the works of suicides, among them Benjamin, Klaus Mann, Koestler, Zweig, Tucholsky. He copies out, in shorthand, hundreds of their pages. And finally, on a mild winter afternoon, he puts on a windbreaker that he has not worn since his early teaching days forty years before, and goes out to stretch himself across the train tracks, awaiting his own (as it were) deportation. Years after this event, looking through Paul's photo album with its record of childhood and family life, Sebald again reflects: "it truly seemed to me, and still does, as if the dead were coming back"--but now he adds, "or as if we were on the point of joining them."

Two tales, two suicides. Yet suicide is hardly the most desolating loss in Sebald's broader scheme of losses. And since he comes at things slant, his next and longest account, the history of his aunts and uncles and their emigration to the United States in the 1920s--a period of extreme unemployment in Germany--is at first something of a conundrum. Where, one muses, are those glimmers of the Jewish ghosts of Germany, or any inkling of entanglement with Jews at all? And why, among these steadily rising German-American burghers, should there be? Aunt Fini and Aunt Lina and Uncle Kasimir, Aunt Theres and Cousin Flossie, "who later became a secretary in Tucson, Arizona, and learnt to belly dance when she was in her fifties": these are garden-variety acculturating American immigrants; we know them; we know the smells of their kitchens; they are our neighbors. (They were certainly mine in my North Bronx childhood.) The geography is familiar--a photo of a family dinner in a recognizable Bronx apartment (sconces on the wall, steam-heat radiators); then the upwardly mobile move to Mamaroneck, in Westchester; then the retirement community in New Jersey. To get to Fini and Kasimir, drive south from Newark on the Jersey Turnpike and head for Lakehurst and the Garden State Parkway. In search of Uncle Adelwarth in his last years: Route 17, Monticello, Hurleyille, Oswego, Ithaca. There are no ghosts in these parts. It is, all of it, plain-hearted America.

But turn the page: here are the ghosts. A photo of Uncle Kasimir as a young man, soon after his apprenticeship as a tinsmith. It is 1928, and only once in that terrible year, Kasimir recounts, did he get work, "when they were putting a new copper roof on the synagogue in Augsburg." In the photo Kasimir and six other metal workers are sitting at the top of the curve of a great dome. Behind them, crowning the dome, are three large sculptures of the six-pointed Star of David. "The Jews of Augsburg," explains Kasimir, "had donated the old copper roof for the war effort during the First World War, and it wasn't till '28 that they had the money they needed for a new roof." Sebald offers no comment concerning the fate of those patriotic Jews and their synagogue a decade on, in 1938, in the fiery hours of the Nazis' so-called Kristallnacht. But Kasimir and the half-dozen tinsmiths perched against a cluster of Jewish stars leave a silent mark in Sebald's prose: what once was is no more.

After the roofing job in Augsburg, Kasimir followed Fini and Theres to New York. They had been preceded by their legendary Uncle Ambros Adelwarth, who was already established as a major domo on the Long Island estate of the Solomon family, where he was in particular charge of Cosmo Solomon, the son and heir. Adelwarth helped place Fini as a governess with the Seligmanns in Port Washington, and Theres as a lady's maid to a Mrs. Wallerstein, whose husband was from Ulm in Germany. Kasimir, meanwhile, was renting a room on the Lower East Side from a Mrs. Litwak, who made paper flowers and sewed for a living. In the autumn, succahs sprouted on all the fire escapes. At first Kasimir was employed by the Seckler & Margarethen Soda and Seltzers Works; Seckler was a German Jew from Brunn, who recommended Kasimir as a metal worker for the new yeshiva on Amsterdam Avenue. 'The very next day," says Kasimir, "I was up on the top of the tower, just as I had been on the Augsburg Synagogue, only much higher."

So the immigrants, German and Jewish, mingle in America much as Germans and Jews once mingled in Germany, in lives at least superficially entwined. (One difference being that after the first immigrant generation the German-Americans would not be likely to continue as tinsmiths, just as Mrs. Litwak's progeny would hardly expect to take in sewing. The greater likelihood is that a Litwak daughter is belly dancing beside Flossie in Tucson.) And if Sebald means for us to feel through its American parallel how this ordinariness, this matter-of-factness, of German-Jewish coexistence was brutally ruptured in Germany, then he has succeeded in calling up his most fearful phantoms.

Yet his narrative continues as impregnable here as polished copper, evading conclusions of any kind. Even the remarkably stoic tale of Ambros Adelwarth, born in 1896, is left to speak for itself-- Adelwarth, who, traveling as valet and protector and probably lover of mad young Cosmo Solomon, dutifully frequented the polo grounds of Saratoga Springs and Palm Beach, and the casinos of Monte Carlo and Deauville, and saw Paris and Venice and Constantinople and the deserts on the way to Jerusalem. Growing steadily madder, Cosmo tried to hang himself and at last succumbed to catatonic dementia. Uncle Adelwarth was obliged to commit him to a sanitorium in Ithaca, New York, where Cosmo died--the same sanitorium to which Adelwarth, with all the discipline of a lifetime, and in a strange act of replication, later delivered himself to paralysis and death.

The yeshiva on Amsterdam Avenue, the Solomons, Seligmanns, Wallersteins, Mrs. Litwak and the succahs on the Lower East Side: this is how Sebald chooses to shape the story of the emigration to America of his Catholic German relations. It is as if the fervor of Uncle Adelwarth's faithful attachment to Cosmo Solomon were somehow a repudiation of Gershom Scholem's thesis of unrequited Jewish devotion; as if Sebald were casting a posthumous spell to undo that thesis.

And now on to Max Ferber, Sebald's final guide to the deeps. Ferber was a painter whom Sebald got to know-- "befriended" is too implicated a term for that early stage--when the 22-year-old Sebald came to study and teach in Manchester, an industrially ailing city studded with mainly defunct chimneys, the erstwhile black fumes of which still coated every civic brick. That was in 1966; my own first glimpse of Manchester was nine years before, and I marveled then that an entire metropolis should be so amazingly, universally charred, as if brushed by a passing conflagration. (Later Sebald will tell us that in its bustling heyday Lodz, in Poland--the site of the Lodz Ghetto, a notorious Nazi vestibule for deportation--was dubbed the Polish Manchester, at a time when Manchester, too, was booming and both cities had flourishing Jewish populations.) At 18, Ferber arrived in Manchester to study art and thereafter rarely left.

It was the thousands of Manchester smokestacks, he confided to the newcomer Sebald, that prompted his belief that "I had found my destiny." "I am here," he said, "to serve under the chimney." In those early days Ferber's studio, as Sebald describes it, resembled an ash pit: "when I watched Ferber working on one of his portrait studies over a number of weeks, I often thought that his prime concern was to increase the dust...that process of drawing and shading [with charcoal sticks] on the thick, leathery paper, as well as the concomitant business of constantly erasing what he had drawn with a woollen rag already heavy with charcoal, really amounted to nothing but a steady production of dust."

And in 1990, when Sebald urgently undertook to search out the life of the refugee Max Ferber and the history of his lost German Jewish family, he seemed to be duplicating Ferber's own pattern of reluctant consummation, overlaid with haltings, dissatisfactions, fears and erasures: "not infrequently I unraveled what I had done, continuously tormented by scruples that were taking tighter hold and steadily paralysing me. These scruples concerned not only the subject of my narrative, which I felt I could not do justice to, no matter what approach I tried, but also the entire questionable business of writing. I had covered hundreds of pages....By far the greater part had been crossed out, discarded, or obliterated by additions. Even what I ultimately salvaged as a 'final' version seemed to me a thing of shreds and patches, utterly botched."

All this falls out, one imagines, because Sebald is now openly permitting himself to "become" Max Ferber; or, to put it less emblematically, because in these concluding pages he begins to move, still sidling, still hesitating, from the oblique to the head-on; from intimation to declaration. Here, terminally--at the last stop, so to speak--is a full and direct narrative of Jewish exile and destruction, neither hinted at through an account of a loosely parallel flight from Lithuania a generation before, nor obscured by a quarter Jew who served in Hitler's army, nor hidden under the copper roof of a German synagogue, nor palely limned in Uncle Adelwarth's journey to Jerusalem with a Jewish companion.

Coming on Max Ferber again after a separation of twenty years, Sebald is no longer that uncomprehending nervous junior scholar fresh from a postwar German education: he is middle-aged, an eminent professor in a British university, the author of two novels. And Ferber, nearing 70, is now a celebrated British painter whose work is exhibited at the Tate. The reunion bears unanticipated fruit: Ferber surrenders to Sebald a cache of letters containing what is, in effect, a record of his mother's life, written when the 15-year-old Max had already been sent to safety in England. Ferber's father, an art dealer, and his mother, decorated for tending the German wounded in the First World War, remained trapped in Germany, unable to obtain the visas that would assure their escape. In 1941 they were deported from Munich to Riga in Lithuania, where they were murdered. "The fact is," Ferber now tells Sebald, "that tragedy in my youth struck such deep roots within me that it later shot up again, put forth evil flowers, and spread the poisonous canopy over me which has kept me so much in the shade and dark." Thus the latter-day explication of "I am here to serve under the chimney," uttered decades after the young Sebald loitered, watchful and bewildered, in the exiled painter's ash-heaped studio.

The memoir itself is all liveliness and light. Sebald recreates it lyrically, meticulously from, as we say, the inside out. It begins with Luisa and Leo Lanzberg, a little brother and sister in the village of Steinach, near Bad Kissingen, where Jews have lived since the 1600s. ("It almost goes without saying," Sebald interpolates-- it is a new note for him--"that there are no Jews in Steinach now, and that those who live there have difficulty remembering those who were once their neighbors and whose homes and property they appropriated, if indeed they remember them at all.") Friday nights in Steinach juxtapose the silver Sabbath candelabrum with the beloved poems of Heine. The day nursery, presided over by nuns, excuses the Jewish children from morning prayers. On Sabbath afternoons in summer, before the men return to the synagogue, there is lemonade and challah with corned beef. Rosh Hashanah; Yom Kippur; then the succah hung with apples and pears and chains of rose hips. In winter the Jewish school celebrates both Hanukkah and the Reich. Before Passover "the bustle is dreadful." Father prospers, and the family moves to the middle-class world of Kissingen. (A photo shows the new house: a mansion with two medieval spires. Nevertheless several rooms are rented out.)

And so on and so on: the blessing of the ordinary. Luisa grows into a young woman with suitors; her Gentile fiance dies suddenly, of a stroke; a matchmaker finds her a Jewish husband, Max's father. "In the summer of 1921," Ferber's mother writes, "soon after our marriage, we went to the Allgau...where the scattered villages were so peaceful it was as if nothing evil had ever happened anywhere on earth." Sebald, we know, was born in one of those villages.

In 1991, fifty years after the memoirist was deported to Riga, Sebald visits Steinach and Kissingen. In the old Jewish cemetery in Kissingen, "a wilderness of graves, neglected for years, crumbling and gradually sinking into the ground amidst tall grass and wild flowers under the shade of trees, which trembled in the slight movement of the air," he stands before the gravestones and reads the names of the pre-Hitler dead, Auerbach, Grunwald, Leuthold, Seeligmann, Goldstaub, Baumblatt, Blumenthal, and thinks how "perhaps there was nothing the Germans begrudged the Jews so much as their beautiful names, so intimately bound up with the country they lived in and with its language." He finds a more recent marker: a relative of Max Ferber's who, in expectation of the outcome, took her own life. (The third suicide in Sebald's quartet.) And then he flees: "I felt increasingly that the mental impoverishment and lack of memory that marked the Germans, and the efficiency with which they had cleaned everything up, were beginning to affect my head and my nerves." A sign on the cemetery gates warns that vandals will be prosecuted.

The Emigrants (an ironically misleading title) ends with a mental flash of the Lodz Ghetto: the German occupiers feasting, the cowed Jewish slave laborers, children among them, toiling for their masters. In the conqueror's lens Sebald sees three young Jewish women at a loom and recalls "the daughters of night, with spindle, scissors and thread." Here, it strikes me, is the only false image in this ruthlessly moving and profoundly honest work dedicated to the recapture of phantoms. In the time of the German night, it was not the Jews who stood in for the relentless Fates, they who rule over life and death. And no one understands this, from the German side, more mournfully, more painfully, than the author of these sad and subterranean recreations.

~~~~~~~~

By Cynthia Ozick

Cynthia Ozick's new novel, "The Puttermesser Papers," will be published by Knopf in the spring.